GF Viewpoint | Context and Complexity 2.0

Context and Complexity 2.0: How does the Coronavirus Pandemic Affect Your China Strategy?

By Edward Tse

March, 2020

Source: Google

Foreign companies have been operating in China since the country started its reforms and opening up of the economy several decades ago, especially after Deng Xiaoping's now well-known "Southern Tour" in 1992. Droves of foreign companies have come to China – some using it as a production base for exports, some making China a part of their supply chains and some tapping into the domestic market.

China's context (its geopolitical, social, regulatory, economic and infrastructure conditions) and complexity (its size, speed of change and heterogeneity) are critical inputs to any company's China strategy and supply chain considerations. As China evolves, these conditions will also evolve, and so should any China strategy.

The recent coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak has created a major discontinuity in China's context and complexity. The conditions for doing business in China are now very different, and many global CEOs are now asking the question, "How should my China strategy change?"

The Paths Working towards the Coronavirus Outbreak

Over the past several decades, the China market has changed significantly. With an average GDP growth of nearly 10 percent in the last couple of decades, China's contribution to global economic growth has grown to almost 30 percent in 2018.[1] Over 850 million people have been lifted out of poverty[2] and the middle class, once only 4 percent of population in 2002, has grown to account for 31 percent of the population according to current estimates.[3] Demand patterns have grown to become much more diversified, with segments stretching to and from the top and bottom ends of the market. Enabled by the rising prevalence of technology, especially the smartphone and wireless internet, private entrepreneurs have driven bouts of disruptive innovations and now account for more than 60 percent of GDP growth.[4] According to the Trust Barometer annual survey conducted by public relations advisory firm, Edelman, China has scored the highest in the world in terms of people's trust in their governments three years in a row (2018 – 2020), among all countries surveyed.[5]

However, in this burgeoning market landscape, foreign companies have achieved mixed results from their China businesses. Take the automotive industry as an example, while foreign premium brands continue to command major market share in the premium market, many mid-range foreign brands have suffered from a lukewarm response from the consumer.[6] In the retail sector, there are a long list of foreign brands that have either left or have sold the majority of their share to Chinese entrepreneurs or companies (Home Depot, Tesco, Marks & Spencer, Auchan, Carrefour, and others). Still, Sam's Club and Costco seem to be doing well in China and Australian food retailer Coles plans to invest further in China this year.[7]

With rapid evolution of China's market, it has become clear that the "old game" does not work anymore. In the past, many foreign companies used to cut-and-paste their business models from home that have been successful for decades, assuming they would work just as well in China. In some cases, this has worked out but in many other cases, it has not. Many companies have failed to appreciate the rapid development and increasing sophistication of the China market, the fast-changing and heterogeneous customer demand patterns, the prevalence of technology and innovations, the intensive competition often epitomized by the rise of local competitors, and most of all, the quickly shifting regulatory, policy and geopolitical conditions.

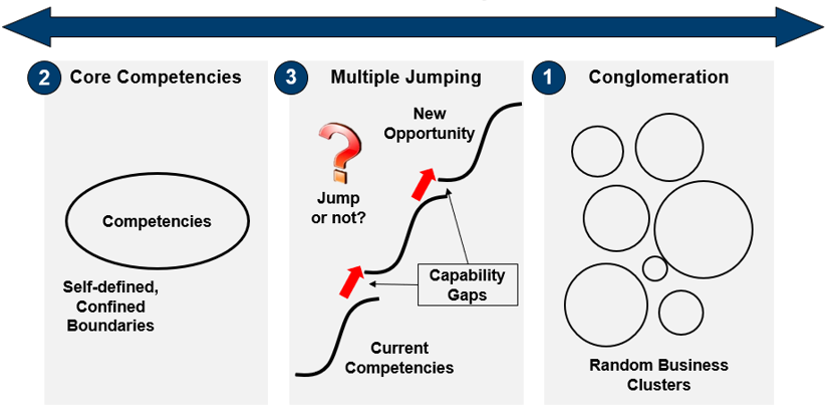

While some foreign MNCs still enjoy relative advantages in industries such as microchips, premium cars, patented drugs and top-end sporting goods, local companies have ramped up in e-commerce, fintech, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) and logistics. In these areas, local companies have emerged as bona-fide competitors to their foreign counterparts. Often, they started as small "insurgents" – seemingly showing up from nowhere – but have strengthened quickly. Through a “multiple jumping” approach, many local companies have crisscrossed from one sector to another by leveraging underlying technologies such as the wireless internet, and now increasingly, artificial intelligence, the internet-of-things, 5G and blockchain, jumping when they see new opportunities (see Exhibit 1). Even though they may not have all the capabilities needed to navigate in the new space, they try to fill the capability gaps along the way.

Exhibit 1

Three Ways of Strategy

Source: Gao Feng Analysis

On a global scale, the world's two leading economies – US and China – are gravitating towards a "G2". Geopolitical events such as the trade war with the US have significantly influenced many companies’ businesses in China. In technology development and adoption, while there is much room for the two countries to collaborate, there are also signs of divergence whereby a scenario of "one world, two systems" is emerging.[8] The underlying differences between regulations, consumer needs, market and competitive dynamics and most importantly, digital infrastructure in these two countries require many global companies to consider different strategic approaches.

While China has been steadily and gradually opening up different market sectors for foreign participation over the last several decades, the recent US - China trade war has accelerated China's pace to increase market access to foreign companies. For those who are in sectors that have been closed, or partially open, China's new and likely future rounds of market liberalization will present an opportunity to tap into what could be a real and sizeable potential.

Recently, regulations have been loosened in the automotive industry. Riding on these initiatives, electric vehicle maker Tesla has opened a new Gigafactory in Shanghai, which is the first wholly foreign-owned auto-manufacturing plant in China. It has received support from Shanghai authorities for accessing land and around $1.5 billion in funding from Chinese banks[9] for the plant. New policies are creating more openness in other sectors as well. The Chinese government has allowed full foreign ownership of insurance companies and banks, and most recently, asset management and securities firms.[10] Foreign participation is now also allowed in oil and gas exploration and production.[11] In January 2019, British multinational BT became the first non-Chinese telecom firm to acquire a nationwide operating license in China.[12]

Whether the opportunity will be a blessing or a curse hinges on one's strategy and execution. Although some foreign players have struggled or even failed along the way, many others have made it. Some continue to expand their operations in China and for some, their China businesses have become their most valuable business globally. What enables a company to capture its full potential in China and what determines its failure to do so?

For a long time, pundits have attributed these reported failures of foreign, especially American, firms in China, to "alleged" unfair trade practices, forced technology transfers and disproportionate support for domestic companies. While these arguments – individually – may not be entirely wrong, collectively they don't adequately explain the range of performance of foreign companies in China. In the Schumpeter column in the June 2018 issue of The Economist, the author correctly pointed out that the victimhood of US companies operating in China was overstated.[13] As different sectors of China's economy become more open, the playing field is becoming more level and competition can often be the most intensive in the world. As such, increasingly, competition is more about one's real capabilities rather than positional advantages or simply endowments from the past. One needs to be truly competitively distinctive in its chosen field to have a real chance to achieve sustainable success in China.

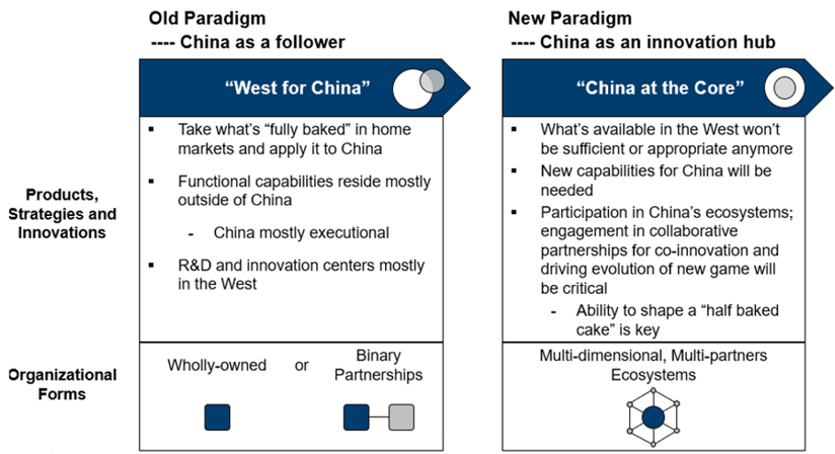

The companies that are capturing the market potential in China have the following characteristics. First, they recognize that China's market demand has changed in sophistication and segmentation, so a one-size-fits-all from the rest of the world probably will not work. They also recognize that in China, business innovations enabled by technology have become prevalent in shaping both the demand and supply sides. Instead of simply taking the innovation results from the West and applying them to China, these successful companies have found that they need to innovate in China for the China market, and increasingly beyond China (see Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2

Innovations: from West to China to China for China (and Beyond)

Source: Gao Feng Analysis

One example of an appropriate strategy is Honeywell's, which has shifted from "West to East" to "East for East". In the 1990s, the company mainly localized low-value production in China for cost advantages. As the markets changed, it moved its Asia headquarters to China, established a position in the mid-segment and sold China-innovated products to other emerging regions. In the future, the company envisions an "East to West" strategy, in which China will become its global growth accelerator.[14]

Companies need to identify their friends and foes and appreciate the value of a "co-opetition" mindset. Against intensive competition with fast and agile local players, foreign companies need to learn to gain speed and agility as well. To complement their capability gaps, collaborative and horizontal partnerships across the ecosystem are as significant as competency itself.

Foreign players must become insiders and adopt a localized approach to the China market. As shown in Exhibit 3, there are three major business circles in China: the first one is associated with foreign companies and organizations such as foreign chambers of commerce; the second one is with the Chinese government and the SOEs; the third one is with local private sector businesses, especially the fast-growing and highly dynamic entrepreneurs. To adequately understand the China context, one needs to fully immerse oneself in all three business circles. Foreign executives should go beyond the foreign business communities to penetrate into the real fabric of the Chinese communities. This way, they can tap deeply into the local landscape so they can appropriately interpret the ever-evolving conditions in China and to anticipate new discontinuities taking place before they manifest themselves. A capable local team that really understands the local context and complexity is a key condition for success for foreign companies in China.

Exhibit 3

China's Three Major Business Circles

Source: Gao Feng Analysis

Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Business Performance and Supply Chains

As the coronavirus continues to spread on a global basis claiming thousands of lives, companies are starting to experience economic repercussions of major lockdowns of entire cities and a slumping of consumer confidence. A recent Shanghai American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) survey covering 109 member companies shows that operations of 48% of companies have already felt the impact on their global operations while 78% of companies are unable to use their production lines fully due to lack of staff. Over the next few months, 58% of companies expect their output to be lower than normal.[15] Food chains such as Starbucks and Yum Brands temporarily closed down thousands of stores across China. Luxury goods are among the most hard-hit industries, and conglomerates like LVMH and Tapestry expect a bigger blow in days to come, until consumer spending recovers fully after digesting the shock. According to China Passenger Car Association, car sales in China tumbled close to 82% year-on-year in February 2020. Many foreign brands, such as Honda and Nissan, are striving to restart production because their joint venture plants are in Hubei Province, where the pandemic was the most severe.[16]

Another major issue arising is the disruption of supply chains. Many companies' supply chain operations are affected and, in many cases, disrupted since China, the original epicenter of the virus is also the epicenter of global supply chains for many companies.

A recent report by The Economist[17] says that most multinational firms have been caught by surprise. They have suffered from temporary closures of their mainland-based suppliers. Big firms will try to ramp up production quickly, but it is unclear how soon the factories can get back to full capacity utilization. Even though many plants are up and running, logistics around and out of China will remain challenging for some more time.

A host of multinationals have signaled missed production targets. Tech giant Apple expects to ship 5% to 10%[18] fewer iPhones this quarter since its largest supplier, Foxconn, had delayed resumption of work. Leading Korean auto manufacturer Hyundai[19] announced in early February that it had to shut down all its factories in South Korea due to a shortage of auto parts from its China-based suppliers. For similar reasons in Japan, several Nissan vehicle manufacturing factories in Kyushu were forced to close.[20]

In response, companies are rushing to make supply chain adjustments. In another Shanghai AmCham survey, which was answered by 127 companies, 87% of respondents believed that the coronavirus would have direct impact on their 2020 revenues. Some mentioned the outbreak increased their determination to move their businesses out of China, to places such as India.[21]

Companies in different industries will react differently since supply chains vary by the nature of specific businesses. For companies in labor-intensive sectors, many had started moving out of China to Southeast Asia or other lower-cost countries due to rising tariffs and other costs even before the outbreak. Some companies with large revenues from the US market have moved their manufacturing operations closer to their US customers by building plants in the US, or to places with lower tariffs and costs than China. However, for companies for which China is an overwhelmingly important market, moving the entire supply chain out of China is difficult and strategically unsound. This is especially true for industries where the supply chains are highly complicated, comprising of a myriad of different suppliers who operate in "clusters" and where "just-in-time" supplies are crucial to the manufacturing operations. Consumer electronics, automotive and advanced machinery exemplify these situations.

Supply chain designs and management are complicated and delicate issues. Over the last few decades, many companies have been deploying their supply chain resources based on the notion of globalization, aiming for an optimal combination of quality, cost and time/responsiveness.

The consecutive external shocks of the US – China trade war and the coronavirus outbreak have put question marks on these assumptions. In the short term, many supply chain operations have been severely affected. Many companies are now scrambling to find short-term stop-gap measures to minimize the downside.

A Glimpse of China in the Post-Pandemic New Global Order

As mentioned above, humanitarian costs and economic casualties have delivered huge shocks to the society. Yet the outbreak is also revealing long-standing societal problems. Many crucial gaps that have been exposed need to be filled urgently. Increasingly, different learned people are sharing their views on how the "New Global Order" would look like after the coronavirus pandemic is over. Inevitably, China's role will remain important.

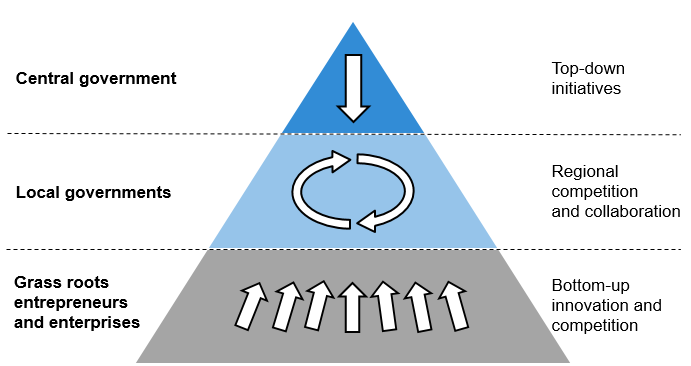

The coronavirus crisis will reshape China in a few dimensions. First, the governance system needs to become more transparent and accountable. Over the past 40 years, China has unwittingly evolved into a three-layer development model to back continued economic success. At the top, the central government sets the national agenda, providing clear directions for the rest of the country. At the grass-roots level, fast-growing and highly dynamic entrepreneurs drive China's growth and innovation. In the middle, local governments compete and cooperate to form regional clusters, while serving as the "glue" between the central government and grass-roots businesses (see Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4

Three-Layered Development Model

Source: Gao Feng Analysis

While this model has proven to be effective in driving China's economic development so far, the coronavirus crisis suggests that it has to broaden its scope beyond the economy, to other aspects of society. In particular, the management of public agenda, such as public health.

After the crisis, governments and companies – whether state-owned, private or foreign – will collaborate across sectors to foster synergies, especially in areas such as smart cities and infrastructure. As an example of what can be achieved, the two new hospitals built in Wuhan – one in 10 days and one in 14 – were the combined effort of state-owned and private enterprises. That was quite a feat.

To push the economy back on track, the Chinese government is set to make major infrastructure investments as a part of a stimulus package. It will also likely implement several measures for industry incentive schemes and may further open market access for non-state companies including foreign owned enterprises. For example, on February 24th, Beijing issued the Strategies for Innovative Development of Smart Vehicles, supporting the development of the smart, connected automotive industry in China.[22]

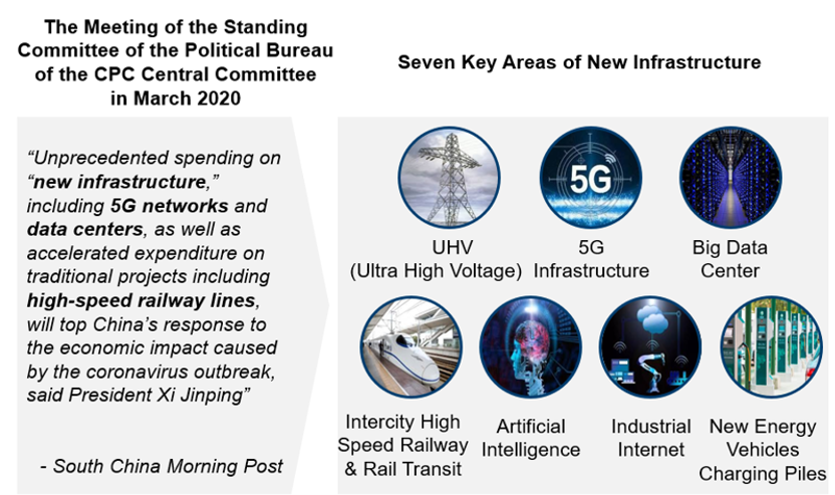

Such moves, however, have been a sort of undercurrent in recent years. The buzzword "New Infrastructure Development", which refers to the series of infrastructure projects launched since 2018, captures the broad policymaking trend towards public welfare agendas (see Exhibit 5). Whereas infrastructure projects in the past focused on high-speed railways, airports and ports, the recent trajectory is "new" in that it focuses on technology upgrades. Specifically, the New Infrastructure Development will encompass 5G infrastructure, ultra-high voltage transmission, new energy vehicles, cross-industry application of big data and artificial intelligence, as well as industrial interconnectivity.

Exhibit 5

“New Infrastructure”

Source: China Daily, South China Morning Post, Gao Feng Analysis

As a result, we will see consequential shifts in three ways. First is a wholesale upgrade of China's smart cities all over the country. These next-generation smart cities will not only address safety and security issues but more importantly, broad public welfare agendas. This will involve the construction of broad connectivity and intelligence infrastructure all over the country. As such, it will also enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of supply chains in China in the future.

Second, the central and local governments will substantially up the ante on public health issues. Beijing recently announced legislative and institutional support to include biosafety in the national security system. Such an effort will take place in conjunction with and be enabled by the major technological advancement and smart city initiatives.

The link between smart city and public health is intuitive. One possible tool to improve disease prevention, early detection, diagnosis and treatment, is for future smart cities to not only track the movement of individuals, but also to identify potential infections (e.g., based on body temperature) and alert nearby health care facilities. Such complex tasks should be implemented through tight integration of the entire big-data-enabled healthcare system, and in coordination among local governments, privately-owned enterprises and state-owned enterprises.

According to the South China Morning Post, China has used surveillance and delivery drones to facilitate the world's largest quarantine to contain the outbreak.[23] At the newly built Huoshenshan Hospital in Wuhan, robots deliver food and medication, sterilize the environment and perform basic diagnostics.

Source: South China Morning Post

In a separate example, tech giant Tencent teamed up with China’s top respiratory diseases expert Dr. Zhong Nanshan, building a big data and artificial intelligence lab to combat the virus. The lab aims to establish a screening mechanism that provides guidance to at-risk populations for certain diseases, using online and offline services that are connected. It will also study how AI can aid diagnostic processes and future outbreaks forecasts.[24]

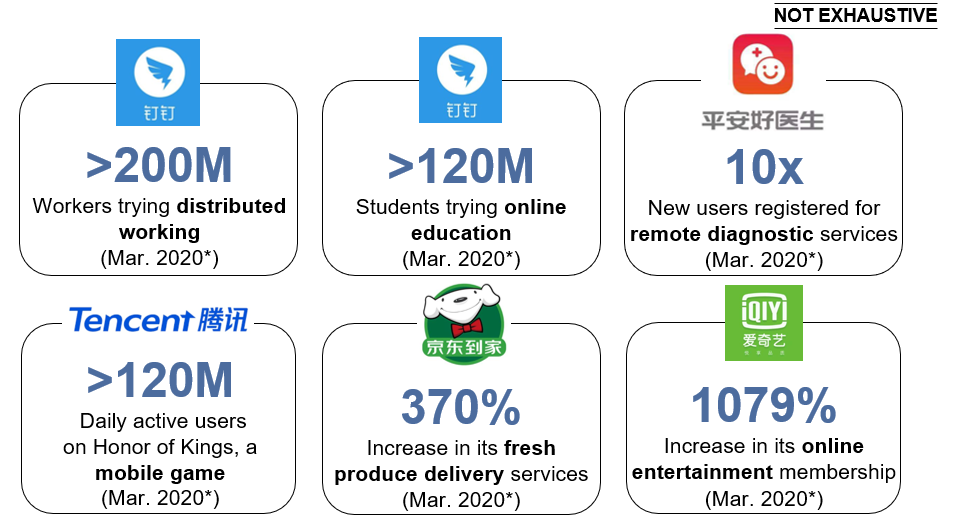

Third, because of the pandemic, the trend of online-to-offline, automation and data-enabled business models is accelerating in the market landscape (see Exhibit 6). Remote working will no longer be seen as an anomaly but increasingly accepted, and online communication platforms will be critical even beyond the times of crisis. For example, Alibaba's remote office and conferencing app DingTalk has performed so well in bringing students back to classes that students flooded the App Store with one-star rating, blaming the app for turning their prolonged vacation into a "miserable experience".[25] In other areas such as entertainment, retail and logistics, automation and robotics will become much more prevalent to boost human-to-machine and machine-to-machine interactions. Smart manufacturing and robotic "last-mile" delivery through autonomous vehicle technology will come out of testing stage soon.

Exhibit 6

Examples of Sharp Increase in Usage for Certain Areas

*Released by respective companies during the Chinese New Year and coronavirus outbreak period, as of Mar. 13th, 2020

Source: Literature Research, Gao Feng Analysis

In summary, global CEOs should expect a very different China under a different global order to emerge after the pandemic. This "New China" will become even more connected and more important for certain aspects of the "New World", but it will also play a major part of the fragmentation in other aspects. Its economy and market will be characterized by more government policy support, more market access to non-state companies, more innovations and disruptions and more public-private partnerships. Novel demand patterns will continue to emerge, with demands surging in some sectors and declining in others.

How Should You Think about Your China Strategy and Supply Chain Deployment?

China means different things to different companies. For some, they came, tried and weren't able to realize their original intentions. Some have sold majority shares to other investors, or simply left the market. Some came and survived through some ups and downs, and their China business has become one of the most important, if not the most important, businesses in their global portfolio. In fact, for many of these companies, their China businesses have implications for other parts of the world, especially other emerging markets. And for others, the China market is finally beginning to open up and they are now facing the prospects of a promising, but challenging, market. Foreign companies with any real global ambitions or appetite for dividends from China’s market need to decide what China means to them. Putting China appropriately in the context of the evolving world will be an important starting point. China has been the largest growth engine in the world since 2006. Global CEOs should examine the criticality of such growth for their companies and whether their current positions will continue to be optimal, especially as the world economy could go into a downward cycle. And in this context, what role will China play in the global economic development in the post-pandemic world? To what extent will China drive new innovations especially in the context of business models and what implications will that have on the structure and competitive conduct of the industry that the company is in? Global CEOs need to figure out what their China strategy ought to be in the evolving China context and complexity, especially after the coronavirus pandemic is over.

As the coronavirus pandemic continues, some companies have decided to make their moves in China. Toyota recently announced collaboration with its local partner FAW Group to build a new electric vehicles plant in Tianjin, China, with a potential investment of $1.22 billion. Starbucks announced that it will invest around $130 million in China to open a roasting facility in 2022, as its first step to build a Coffee Innovation Park to further strengthen its coffee supply in Asia. Apple announced it will keep all its retail stores in Greater China open while closing the ones in the rest of the world temporarily.

The coronavirus pandemic has created a very precarious situation for the world. Some companies are under significant financial pressure and they are in a survival mode. Others need to fix short-term operational issues such as keeping the supply chain and manufacturing operations going. And for others who can look beyond the immediate timeframe, this could be a good opportunity to plan for their next important strategic move(s).

Global CEOs must address the medium- and longer-term priorities of what to do with respect to their China strategy and supply chain. And they will need to answer several fundamental questions:

1. What would the new global order look like post-outbreak and what will be the role of China in this new context?

2. How will the key drivers of my business in China be shifted post-outbreak (e.g., geopolitical, regulatory and policy context, customer profiles and their demand patterns, technologies, innovations, and competitive landscape)?

3. Given the above, what will China mean for my company? Should we double down and invest more? Or should we stay put and milk the business? Or do we simply get out?

4. If we decide to invest, then next questions are how, when, and where. What kinds of capabilities, in particular, innovations, would be needed to drive success in China? How much can be leveraged internally and how much needs to be developed locally on the ground?

5. What organizational approach is needed for the China business? What types of local leadership and team do we need? What is the extent of local empowerment? How to ensure that the global teams and the local team can team up well? What about external partnerships for accessing the needed resources and skills? How could "co-opetition" be an appropriate play in my strategy?

6. What are the key variables that could affect this new strategy and supply chain, e.g., trade tariffs, non-economic trade considerations such as "national security" concerns, supplier base, costs, quality, agility and responsiveness? What are the likely future scenarios? How to prepare for, or at least assess, contingency risks such as a "black swan" event?

For many global companies, creating a winning China strategy and making the right decision for the supply chain deployment are pivotal. A company's China strategy often has major implications for its global success. While the short-term disruptions in China due to the coronavirus pandemic are painful, thinking through the medium- and longer-term strategy requires careful deliberation. The interplay between global dynamics and China's own developmental priorities is putting China and its role in the world at the crossroads and at the cusp of another major discontinuity. While political populism that started well before the pandemic was driving the world in one way, the universal need to address cross-border topics like pandemics, climate change, pollution and technology issues such as AI ethics require collaboration across countries, with China being at the center of the roles and responsibilities. Developing the right China strategy will therefore require a deep understanding of China's new sets of context and complexity. Linear extrapolation from the past will certainly be insufficient. The right answers will need to come from a well-informed and perceptive forward-looking perspective.

References:

1. Xinhua. (August 29th, 2019). China rises to top engine of global economic growth in 70 years. Xinhua News. Retrieved from http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-08/29/c_138348922.htm

2. The World Bank. (December 13th, 2019). The World Bank in China. The World Bank. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview

3. Cyrill, Melissa. (March 28th, 2019). China's Middle Class in 5 Simple Questions. China Briefing. Retrieved from https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-middle-class-5-questions-answered/

4. Xinhua. (March 6th, 2018). China's private sector contributes greatly to economic growth: federation leader. Xinhua News. Retrieved from http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-03/06/c_137020127.htm

5. Edelman. (January 19th, 2020). The Edelman Trust Barometer 2020. Edelman. Retrieved from https://www.edelman.com/trustbarometer

6. Hancock, Tom. (March 4th, 2019). Why Ford is stalling in China while Toyota succeeds. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/6fd5a4c4-36c1-11e9-bd3a-8b2a211d90d5

7. Smith, Michael. (November 7th, 2019). Coles targets China's middle class with prime beef exports. Australian Financial Review. Retrieved from

https://www.afr.com/companies/retail/coles-to-tap-into-china-beef-export-boom-20191107-p538da8. Tse, Edward. & Russo, Bill. (Sep 9th, 2019). Under "one world, two systems", US companies that stay in China must evolve. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3030158/under-one-world-two-systems-us-companies-stay-china-must-evolve

9. Roberts, Chris. (January 7th, 2020). Inside Elon Musk's Amazing Chinese Adventure—And Tesla's Big Win. Observer. Retrieved from https://observer.com/2020/01/elon-musk-china-trip-tesla-model-3-shanghai-production/

10. Liu, Lucille., Rodrigues, Jeanette. & Luo, Jun. (January 23rd, 2020). China's Finance World Opens Up to Foreigners, Sort Of. Bloomberg News. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-01-22/china-s-finance-world-opens-up-to-foreigners-sort-of-quicktake

11. Chen, Aizhu. & Xu, Muyu. (January 9th, 2020). China opens up oil and gas exploration, production for foreign, domestic firms. Reuter. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-oil-mining/china-to-open-oil-gas-exploration-production-to-foreign-firms-idUSKBN1Z806Q

12. CGTN. (Jan 29th, 2019). BT becomes first foreign telecoms firm to secure Chinese license. China Daily. Retrieved from https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201901/29/WS5c4fbdfca3106c65c34e70b2.html

13. Schumpeter. (June 28th, 2018). American Inc and the rage against Beijing. The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/business/2018/06/28/america-inc-and-the-rage-against-beijing

14. Honeywell. (June, 2012). Morgan Stanley China Investor Summit. PDF. Retrieved from

http://investor.honeywell.com/Cache/1500080460.PDF?O=PDF&T=&Y=&D=&FID=1500080460&iid=412134615. Bermingham, Finbarr. (February 17th, 2020). Coronavirus: American factories in China unable to staff production lines as lockdown continues. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3050984/coronavirus-american-factories-china-unable-staff-production

16. Wayland, Michael. (February 10th, 2020). Automakers resume or prepare to restart car production in China amid coronavirus outbreak. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/10/ford-gm-resume-or-prepare-to-restart-china-car-plants-amid-coronavirus.html

17. Vaitheeswaran, Vijay. (February 15th, 2020). The new coronavirus could have a lasting impact on global supply chains. The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/international/2020/02/15/the-new-coronavirus-could-have-a-lasting-impact-on-global-supply-chains

18. Mickle, Tripp. (February 5th, 2020). Rapid spread of coronavirus tests Apple's China dependency. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/rapid-spread-of-coronavirus-tests-apples-china-dependency-11580910743

19. Leggett, Dave. (February 5th, 2020). Hyundai to shut down South Korean plants this week. Just-Auto. Retrieved from https://www.just-auto.com/news/hyundai-to-shut-down-south-korean-plants-this-week_id193493.aspx

20. Xu, Zhe. (February 28th, 2020). Auto companies resume work one after another, but the impact of the epidemic has spread worldwide. Guancha Net. Retrieved from https://new.qq.com/omn/20200228/20200228A0HKV600

21. Chow, Emily. (February 7th, 2020). Majority of U.S. firms in China see revenue hit from coronavirus: AmCham survey. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-survey/majority-of-u-s-firms-in-china-see-revenue-hit-from-coronavirus-amcham-survey-idUSKBN20118Q

22. National Development and Reform Commission. (February 24th, 2020). Notice on Printing and Distributing the "Smart Car Innovation and Development Strategy. National Development and Reform Commission. Retrieved from https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/tz/202002/t20200224_1221077.html

23. Liu, Yujin. (March 5th, 2020). China adapts surveying, mapping, delivery drones to enforce world's biggest quarantine and contain coronavirus outbreak. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/business/china-business/article/3064986/china-adapts-surveying-mapping-delivery-drones-task

24. Chen, Celia. (February 28th, 2020). Tencent teams up with 'Sars hero' Zhong Nanshan on AI, big data lab to combat coronavirus and predict outbreaks. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from

https://www.scmp.com/tech/science-research/article/3052866/tencent-teams-sars-hero-zhong-nanshan-ai-big-data-lab-combat

25. Jao, Nicole. (March 2nd, 2020). Dingtalk begs for stars on China's app store. Technode. Retrieved from https://technode.com/2020/03/02/dingtalk-begs-for-stars-on-chinas-app-stores/

About the Author

Dr. Edward Tse is founder and CEO, Gao Feng Advisory Company, a founding Governor of Hong Kong Institution of International Finance and Adjunct Professor, School of Business Administration, Chinese University of Hong Kong. One of the pioneers in China’s management consulting industry, he built and ran the Greater China operations of two leading international management consulting firms for a period of 20 years. He has consulted to hundreds of companies – both headquartered in and outside of China – on all critical aspects of business in China and China for the world. He also consulted to the Chinese government on strategies, state-owned enterprise reform and Chinese companies going overseas, as well as to the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. He is the author of several hundred articles and four books including both award-winning The China Strategy (2010) and China’s Disruptors (2015) (Chinese version «创业家精神»).

Gao Feng Advisory

Gao Feng Advisory Company is a professional strategy and management consulting firm with roots in China coupled with global vision, capabilities, and a broad resources network

Wechat Official Account:Gaofengadv

Shanghai Office

Tel: +86 021-63339611

Fax: +86 021-63267808

Hong Kong Office

Tel: +852 39598856

Fax: +852 25883499

Beijing Office

Tel: +86 010-84418422

Fax: +86 010-84418423

E-Mail: info@gaofengadv.com

Website: www.gaofengadv.com

Weibo: 高风咨询公司