GF Viewpoint | First Time in History

First Time in History: China's Unprecedented Social and Economic Development

An Interview with John D. Van Fleet

December 2021

Preface

On December 21, 2021, I had a dialogue with John D. Van Fleet, Director, Corporate Globalization at Antai College of Economics & Management, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. In this dialogue, we discussed on China's unprecedented social and economic development.

Edward Tse (hereinafter Ed): Today, we’re really privileged to have Professor John Van Fleet with us. Hi John!

John D. Van Fleet (hereinafter John): Hey, how are you?

Ed: Good! Professor Van Fleet is the Director of Corporate Globalization at Antai College of Economics and Management of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. I’ve known Professor Van Fleet for quite a number of years. We have had several conversations and dialogues. I’ve made presentations to the school and I’ve always found it an intellectually fulfilling opportunity to chat with Professor Van Fleet. I’m going to call him just John today because we’re not that formal.

I have known John for several years but recently I've come across an idea from John that he called “First Time in History”. I found it very intriguing and very relevant for a large part of our audience and clients.

So today, I’ve asked John to join us in this webcast so that he can tell us more about this concept. Perhaps, John, could you tell us about what “First Time in History” is and how you came up with this concept?

John: Sure. Thank you, Ed. It’s a privilege and honor to be here to talk to you. I think we first met after I read your book some years ago. I was quite pleased to incorporate it in the seminars I lead at Antai College.

Those seminars, in turn, are where the “First Time in History” idea got started really. It’s not new and it’s not mine. There have been other people who have talked about this concept before.

Jonathan Fenby has written a great book called “Tiger Head, Snake Tails” and its first chapter is titled “Never Before”, so this idea has been out there. But I wanted to find a way to help our delegates that come from all over the world to our campus here in Shanghai to understand it in a constructed and comprehensive way - what’s happening in China socioeconomically, macroeconomically?

What is it that they can use as a frame to understand what’s happening here? So, I came up with the title “First Time in History” because I think we all agree, that it’s incontrovertible, that what has happened in China since 1978 has “Never Before” happened at any time in human history, not even close, in terms of scale, scope and speed.

Ed: So, what evidence have you observed to support your thesis, John?

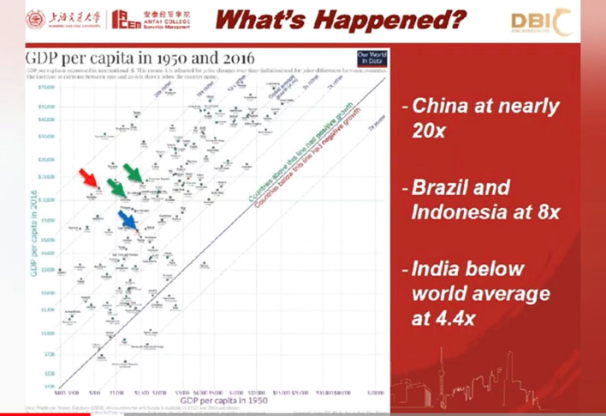

John: Well, a couple of things. Probably the most easily-identified one is per capita GDP. Looking at per capita GDP growth from the late 70s until recent years. Part of China’s explosive growth is because they started from a very low baseline - 1978 was a pretty low point for per capita GDP in China. Since that time, and these statistics are widely available, China’s per capita GDP has increased by more than 20 times on a PPP basis.

You wouldn’t expect an industrialized country to have that kind of growth. The proper comparison is with developing economies such as Brazil, Indonesia, and India, which are other large population developing economies.

China’s growth over these decades has been about double that of Brazil and Indonesia and about four times what India’s growth has been. That’s a pretty dramatic number.

China’s per capita GDP growth (red) has exceeded that of Brazil and Indonesia (green) and especially that of India (blue)

Ed: Right.

John: But you can look at other metrics such as literacy rate, life expectancy, percentage of people living in poverty, and other demographic metrics – they reinforce the conclusion that what’s happened here in China in the recent past, since 1978, which is the watershed, is extraordinary. Again, it’s the “First Time in History” phenomenon. We’ve never seen this kind of development this fast and this far.

Ed: And could I also ask that - how many years you’ve been working in China now, John?

John: I’ve been living here for a bit more than 20 years. I first started doing business in China in the mid-90s.

Ed: So, you have seen this in person. This is not from reading some reports by others. This is your personal experience, isn’t it?

John: Well, I have been here a while, and I’ve been working at the school for most of the 20 years, at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. I’ve been fortunate enough to visit more than half of China’s provinces. I’ve been around a bit, but I think for me, what’s most important is the perspectives of Chinese people from a lot of different walks of life - whether they’re older or younger. To understand China’s macroeconomic transformation through the lives of Chinese people. That’s where I think the story is most powerfully visible.

Ed: Yeah, that’s wonderful because we have come across many types of people over the years, and lots of them have talked about China, but I’d say some people talk about China from a long distance.

They were looking at China with binoculars. But there are people like you, who’ve been looking at China, witnessing China, in person in the country through interactions with people from many walks of life. I think that makes a big difference. Would you agree?

John: Well, I’m kind of biased, I do kind of like to think so. I feel like I’ve been very fortunate to be here. I tell my friends in other parts of the world, even here, that I feel like, having been here for 20 years, I’ve had a front-row seat for the 21st century. It’s a remarkable opportunity to be here. I do think I’ve gained some incremental perspective, having been on the ground, being around China, knowing people here, and doing business here. That does help.

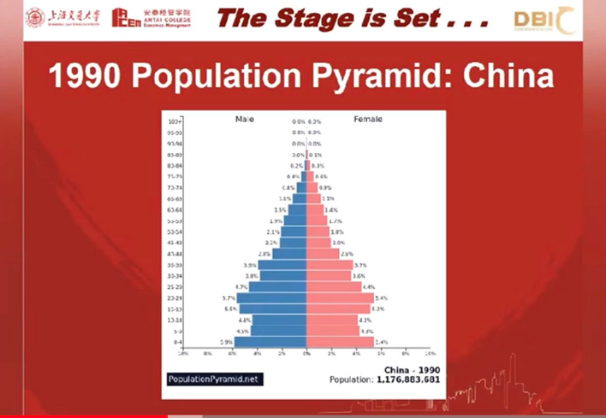

China’s population pyramid more closely resembles those of developed economies, narrower at the bottom, fatter at the top, and an indication of longer life expectancy

Ed: So, why did “First Time in History” happen? What happened after this phenomenon?

John: Again, I can’t claim any originality to this, while I do think I’ve done some work to pull the threads together. In 1978, China was just coming off the cultural revolution. Mao Zedong had died two years before. It was an abjectly poor place with a shattered economy in many ways. So, part of the reason that China’s growth has been so spectacular is that the baseline was very low.

Ed: Yeah.

John: But in 1978, China already had some promising demographics, and those promising demographics were in the shape of the population curve. China had its baby boom that started in the early 60s and that population was on the verge of entering the workforce, so there was a demographic bubble that benefitted China in the 80s, the 90s, and into the 2000s. This pool of available labor was a major contributor to manufacturing for export, which was the primary driver of China’s growth until the great financial crisis of 2008.

Also by 1978, literacy in China was uncommonly high for a developing economy, particularly for women. Chinese women had a much higher literacy rate than the women of India, for example, by the late 70s. A promising level of education empowered people to be more effective employees in manufacturing enterprises. Leslie Chang tells this story tremendously in her book “Factory Girls”, which was published 15 years ago, about the degree to which the migrant labor population, that started working in manufacturing in the late 80s and into the 2000s, was female. Because they had received a better education than some of their sisters in other developing economies, these women could be major participants in the manufacturing for the export economy.

Thus, a demographic bubble of younger people, relatively well-educated and ready to work, and a longer life expectancy than in Indonesia or India by the early 80s constituted a promising demographic base to build on.

Then starting in 1978, you had three essential pieces to the growth trajectory. One of them was some pretty smart government initiatives, famously in the era of Deng Xiaoping, the early era of reform and opening up. Two policy features, in particular, stand out –the “town and village enterprise system” and the “household responsibility system”. Both devolved decision-making from the state level to the community, household, and individual levels, allowing Chinese entrepreneurship to flourish. And the second piece, which is the entrepreneurial spirit of people here, is tremendous, as anybody who’s been here can attest.

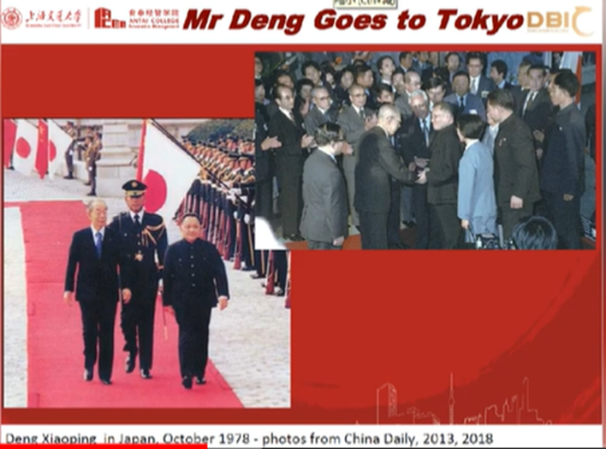

So, some pretty smart government initiatives started in the late 1970s. A remarkable spirit of entrepreneurship. The third piece was global engagement. In October 1978, Deng Xiaoping went to Japan, an economy that had been shattered by the war and had rebuilt itself quickly.

Deng met Japanese business and government leaders, including prime minister Fukuda, and the founder and CEO of Matsushita. He told them that China had two powerful resources: a lot of people who were relatively well educated, and a lot of land and raw materials. But what China lacked was money and technology. Deng invited Japanese enterprises to join China for mutual benefit.

And the Japanese enterprises increasingly said yes and then so did economies from elsewhere in the world, most notably from Taiwan. The Taiwanese came here in large numbers in the 80s, with the common language being a massive advantage.

So some smart government initiatives started the process of change and opening up and reform. Another factor was the great entrepreneurial spirit of the Chinese people, the rocket fuel for China’s development. And the third one was re-engagement with the world which brought in an enormous amount not just as FDI, which is not just funds but more importantly technology transfer and people learning how to engage in a global economy. Matsushita took 250 Chinese engineers to their facility outside of Osaka in the early 80s after Deng’s visit, and that number got multiplied by one million over the coming few decades– the number of young Chinese aspirants who gained global skills and global mindsets.

Ed: Yeah, John, this is fantastic. It reminds me of the days in the early 90s when I returned to Shanghai to practice strategy and management consulting. As you know I was with Bob Ching who was the pioneer in the consulting profession in China. Bob was leading the Boston Consulting Group in China. I joined him and we worked together. That was a really good time because that was around the time when Deng Xiaoping came back from Japan, and he came to Shanghai and Shenzhen to visit and to remind people that reform and opening-up were critical. Thus, a lot of multinational companies came to China and tried to explore the China market. As Boston Consulting Group is a global consulting firm, many of our projects came from various multinational companies and we were asked to help them understand China.

But frankly, the most interesting part, for me, was the Chinese entrepreneurs and their companies. In general, they were very interested in finding out how they could improve and be more competitive. At that time many of the companies were very rudimentary from today’s standards. They were nascent in their development, but their curiosity and interest in learning was significant and evident. They came to us and they viewed us as a conduit to the external world for understanding business management. Of course, 30 years later many of them have become very successful, and some even world-class. But I still remember those days. Thanks for reminding me of that because that was a great time and we saw the burst of that entrepreneurial energy in China first-hand.

John: It’s just happening in different ways nowadays and of course, because GDP is now 20 times what it was 40 years ago, we have never seen the year-on-year percentage growth that we saw in the 90s. And there’s no need to, because nowadays a 5%, even a 2%, rise in GDP in monetary terms is equivalent to 20% some years ago, because the economy is so much bigger.

Ed: Yeah, we did some calculations. The size of the economy today grew by 5%, which is equivalent to some G20 economies in the world, like the Netherlands, and Switzerland. So, every year China produces a significant economy of that kind of order, and that is quite incredible.

But you start by tracing the origin in the late mid-70s and then of course it began to evolve into the 80s and 90s and so on. But would your concept still have an experiential value today? Does it still hold today? Because the world has changed so much since 40 years ago. It’s a different world now.

John: We’ve just noted that we’re never going to see year-on-year percentage growth in China of the kind we saw 20, 30 years ago because the baseline is so much higher. But there are still a lot of tectonic forces driving China’s macroeconomic development that are still in play – there are a lot of runways.

So, I like to look at it from the perspective of three different macroeconomic drivers: demographics, infrastructure, and technology. To consider demographics for a moment. Everybody knows there are no longer so many young people and part of that is thought to be the pernicious effect of the one-child policy. But in reality, the policy was probably less of a driver of lower birth rates than is commonly assumed – as women become better educated (and consequently wealthier) get they have fewer children. This phenomenon is worldwide. But the relevant point here is that there are still hundreds of millions of Chinese people who are just coming into what you might call a global consumer, disposable income lifestyle. The Gini coefficient here, the gap between rich and poor is substantial and of great concern, which is one of the reasons the government launched the Common Prosperity campaign. But if you look at rural versus urban disposable income, while the urban is indeed growing.

This growth in rural disposable income suggests that, from a demographic standpoint, there’s still a lot of consumption coming online in China that should not be ignored by anybody who’s trying to think about the likely future here.

On the infrastructure side, the most obvious aspect is the building of the high-speed rail system. There are a lot of economists, including the famous Michael Pettis, who have claimed that the infrastructure build-up achieved its maximum efficiency maybe 10 years ago and a lot of infrastructures are wasteful now. Fair enough, there is an important and interesting macroeconomic discussion about that point, but regardless of that, there is an enormous amount of infrastructure that fosters economic growth in China that didn’t exist 20 years ago, whether it’s rail systems, roads, buildings, airports, sewage systems or electricity. Nearly 40 percent of Chinese households had no electricity 40 years ago and now the electrification rate is like 95 percent. All of these infrastructure features lend themselves to more economic growth now and into the future.

The innovation environment here for technology has been a major driver of China’s macroeconomic rise and will continue to be so for many years to come. One of the foundations of my understanding has been your book which I am happy to have in my hand here. “China’s Disruptors” is a tremendous book and it’s now six years old, right?

John: I highly recommend this book to anybody who wants to understand China’s technology environment because, even though these stories are now getting to be 10 years old, a lot of these companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Huawei, and Xiaomi are still really interesting players in China’s technology environment.

Ed: Absolutely. Thank you, John.

John: Anybody who lives here knows that our entire lives are right here (on your mobile phone) now in a way that just doesn’t happen in any way in most of the rest of the world.

Ed: Do you still carry cash, John?

John: [laughs] I do but I carry it as a sort of antique. And sometimes I have to take a wallet out to get something, maybe an ID card or something, and people say “oh, look! You have cash in there.” It’s an item of conversation. I don’t remember the last time I used cash for anything. But what’s more, it’s not just cash transactions, it’s everything else. The degree to which super apps like Meituan or many others are an essential part of life here. It isn’t just a consumer convenience story. It reduces economic friction which leads to economic growth at a macro scale. That’s pretty important to understanding the economy here.

Ed: Exactly. When we started talking earlier today, we were talking about you being in China. You have witnessed this growth and change in China firsthand and you have talked to many types of people in China. There are also a lot of people outside of China, and they like to talk about China because China is such a good topic to talk about.

Everyone has his or her opinion about it. Being somebody who has been in China for 20 years or more, and as an American very close to China and understanding what’s been going on, what do you think the people who are not in China are missing about China?

John: Ed, I’m glad you asked that because this is a topic near and dear to my heart. My good friend and colleague at Antai College, Nan Li, is a finance faculty at our business school. She did her Ph.D. at the University of Chicago. She has taught globally - she was on faculty at the National University of Singapore for many years. Professor Li and I have just had an essay “Follow the money, not the rhetoric, to make sense of China-U.S. ties” published in Nikkei Asia that speaks exactly this point.

It is a common and daily phenomenon that we will see overseas pundits and overseas media blaring about some aspect of China this, China that, whatever. My conclusion – and I don’t think I’m alone and I'm sure you share this as well, is that a lot of people, especially overseas, are making a lot of noise about what’s happening here that’s not only off point, but that’s missing an important story.

Here’s an example. A lot of recent headlines are talking about decoupling, it’s a big topic, or this or that regulation being the death of Chinese tech evolution. If that were true, you’d probably see that in such things as FDI numbers, businesses, and profitability here. But if you look at those numbers, which is what professor Li and I say in the article, you will see that FDI in China has actually not only been growing at a fairly decent clip, but FDI in China really took off during the COVID-19 time and that China is now the No. 1 global recipient of FDI. Foreign entities with real money to invest, who have skin in the game, know that there's a high-value business opportunity to be captured here and so they’re investing accordingly. They’re voting with their pocketbook as opposed to just a headline.

Another example is the annual surveys of business chambers here, like the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, and the European Chamber China. Their members are business leaders based in China, and the surveys gauge the sentiment of those business leaders. They are not only uniformly optimistic about the business opportunity in China for multinational enterprises, but they are also saying that it’s not just their sentiment – that their actual profitability is strong. The American Chamber of Shanghai’s Sentiment Index is stronger than it’s been in several years. European Chamber members report that their profitability is not just stable and strong but outstripping that of other markets where these companies have businesses. Thus, there’s a lot of real data that argues against the idea of some rumored pernicious economic downturn.

And I think ‘decoupling’ is an oversold story – I think that's not the correct word, it should be recoupling. There’s a lot of real stuff that’s happening on the ground that puts the lie to a lot of headlines we see in some of the major media of the world, and politicians in other parts of the world. Fair enough, they have their domestic audiences to play to. But the reality in China is much different, and it’s much stronger and more promising than we’re commonly led to believe, at least in the Anglophone world.

Ed: Yes. John thanks for the time. I have one final question. You have been doing this research for quite a few years now. You’ve been talking to students, and visitors and you’ve been sharing with them your personal experience. What do you intend to take your research results for and how would you want to make use of them further based on these results and observations that you’ve made over the years?

John: I hope that somebody thinks that this work – which is not just me, it’s a lot of colleagues, friends, and partners collaborating – is worth a very fat book contract and very nice speaking fees all over the world! But beyond any personal potential gain, I hope my friends in the United States, or my friends in Europe, my friends in Japan where I lived for a decade before I came to China, can look at this kind of work and get a different perspective on China than what is commonly and loudly proclaimed in headlines, or by foreign government leaders, or even in the arguments at the national government level between various countries and economies, because there’s a real, extraordinary story here – one that’s changing the world.

It’s “First Time in History” and it has not nearly played out. There are many chapters to come. You can see it in the way that people are living their lives engaged with e-commerce and the way people are living their lives with their discretionary incomes. There’s a lot of room here and I want our work to help people realize that. And hopefully, by doing so, get past the scare stories, the animosity, and the rivalry, and get down to economic cooperation that benefits everybody.

Ed: That’s fantastic, John. I think this is needed and a very noble objective. I wish you the very best of success. I will continue to monitor your research results and hopefully, at some point, I’ll see a book coming out from you on this topic. Thank you again.

John: It’s an honor to be a part of Gao Feng’s platform and to have a chance to talk to you. Thank you very much.

Ed: Thank you.

About the Interviewee

John D. Van Fleet serves as adjunct faculty and Director, Corporate Globalization, at the Antai College of Economics and Management, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, where he focuses on corporate interface and development for the students and the faculty of the College. His research project is First Time in History, an exploration of China’s macroeconomic rise since 1978. For more than ten years, he served as founding executive director and Assistant Dean at the USC Marshall-SJTU Antai Global Executive MBA in Shanghai. Previous to his academic career, Van Fleet spent 15 years in the private sector, based in Japan and China, serving multinationals as well as start-ups.

About the Interviewer

Dr. Edward Tse is founder and CEO, Gao Feng Advisory Company, Adjunct Professor of School of Business Administration at Chinese University of Hong Kong, Professor of Managerial Practice at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, and Adjunct Professor at the SPACE program of University of Hong Kong. He is a member of Global Future Council on China at the World Economic Forum, as well as a member of advisory boards for private equity and venture capital companies. He started his strategy consulting career at McKinsey’s San Francisco office in 1988 before returning to Greater China in the early 1990’s. He became one of the pioneers in China’s management consulting industry, by building and running the Greater China operations of two leading international management consulting firms (BCG and Booz) for a period of 20 years. He has consulted to hundreds of companies, investors, start-ups, and public-sector organizations (both headquartered in and outside of China) on all critical aspects of business in China and China for the world. He has also advised the Chinese government organizations at different levels on strategies, state-owned enterprise reform and Chinese companies going overseas, as well as to the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. He is the author of several hundred articles and five books including both award-winning The China Strategy (2010) and China’s Disruptors (2015), as well as 《竞争新边界》 (The New Frontier of Competition), which was co-authored with Yu Huang (2020). He holds a SM and a SB in Civil Engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as well as a PhD and an MBA from University of California, Berkeley.

Gao Feng Advisory

Gao Feng Advisory Company is a professional strategy and management consulting firm with roots in China coupled with global vision, capabilities, and a broad resources network

Wechat Official Account:Gaofengadv

Shanghai Office

Tel: +86 021-63339611

Fax: +86 021-63267808

Hong Kong Office

Tel: +852 39598856

Fax: +852 25883499

Beijing Office

Tel: +86 010-84418422

Fax: +86 010-84418423

E-Mail: info@gaofengadv.com

Website: www.gaofengadv.com

Weibo: 高风咨询公司